Of course, service providers “know” their networks – fiber optic lines, wireless infrastructure, central office equipment and the last mile connections to their customers – but what’s connected to the networks, often via router end points is another matter. In light of heightened geopolitical tensions, specifically with the recent US and EU acknowledgment of Russian government responsibility on DoS attacks on ISPs, and threats of cyber attacks, it is time to take a fresh look at this issue – that is, the millions of unprotected home and small business networks and the hundreds of millions of computing, personal and IoT devices around the world.

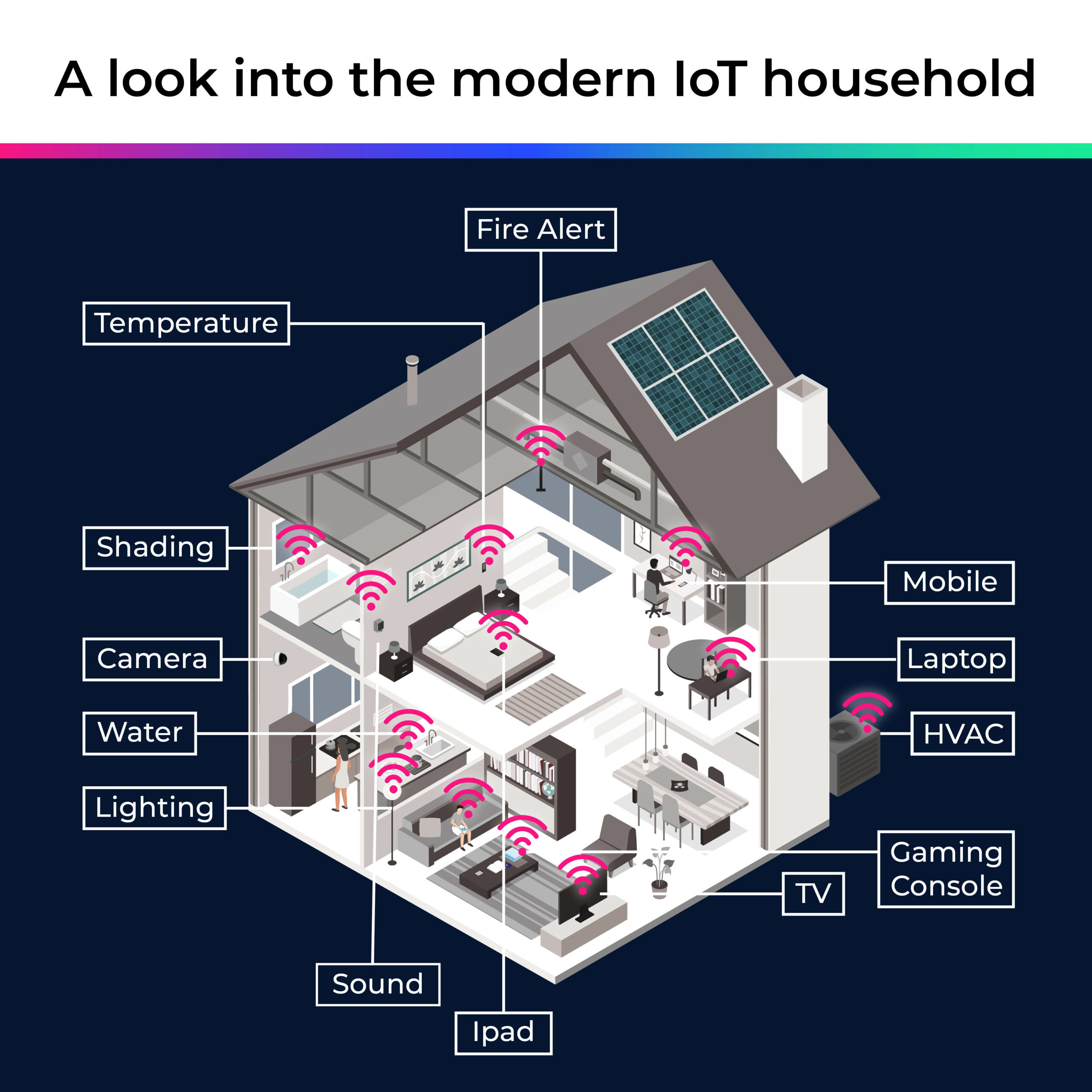

Recent cyber attacks in the news, such as those in Europe involving a well-known satellite-based Internet service provider, have been more or less visible and immediately felt. Another danger involves planting dormant agents, such as botnets, in network connected devices and then activating them sometime later, perhaps weeks, months or even longer, in order to launch a DoS/DDoS attack with potential devastating ramifications. As has been pointed out many a time, many home, SOHO and micro-business devices and networks have little or no protection, for a variety of reasons. Versions of nearly every consumer electronics device, many of which are also present in organizations’ facilities, have become connected IoT devices — security cameras, VoIP phones, kitchen appliances, thermostats, door locks, light bulbs and TVs – and are connected to home routers. Therefore, a sizable service provider could have many tens of millions, of “unknown” IoT devices on their networks.

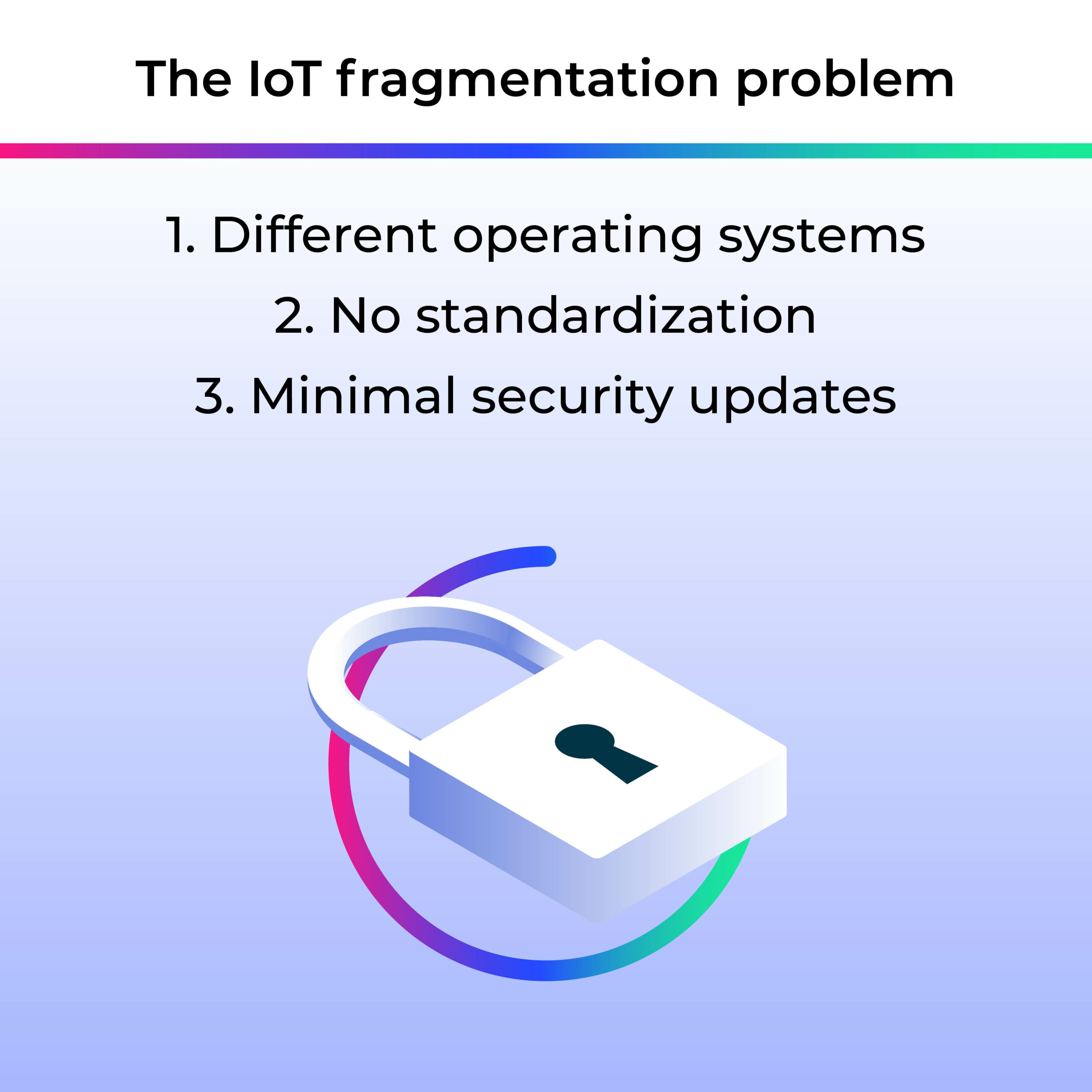

According to the NIST Cybersecurity for IoT Program, there are three main reasons why it is difficult to protect IoT devices:

- Many IoT devices interact with the physical world in ways conventional IT devices usually do not.

- Many IoT devices cannot be accessed, managed, or monitored in the same ways conventional IT devices can.

- The availability, efficiency, and effectiveness of cybersecurity and privacy capabilities are often different for IoT devices than conventional IT devices.

SOHO network equipment at risk – CISA

There has been a predictable wave of cyberattacks leading up to and following Russia’s attack on Ukraine – and hackers seek to exploit vulnerabilities such as these. For instance, the Russian state-sponsored group known as Sandworm recently tried to take down the largest energy provider in Ukraine. In addition, the US CISA recently warned all federal civilian agencies and all US organizations (which would include telecoms services providers) how Sandworm has exploited a “high severity privilege escalation flaw” in order to build a botnet called “Cyclops Blink” out of compromised SOHO network devices made by a leading manufacturer.

There are many other recent examples and attacks such as these that are based on now long-established practices by hackers, some even government-sponsored, who use botnets like Mirai, other vulnerabilities and techniques to gain access to IoT devices and using them as bots in a DDoS attack. For example, the Mirai botnet code infects poorly protected internet devices by using various protocols like telnet, SSH, or HTTP to find those that are still using their factory default username and password. The effectiveness of Mirai is due to its ability to infect tens of thousands of these insecure devices and coordinate them to mount a DDoS attack against a chosen victim.

Furthermore, a report by AT&T Alien Labs in November 2021 identified that the BotenaGo malware is targeting millions of routers and IoT devices with more than 30 different exploits, some of which are almost 10 years old. Malware such as this is based on the “Go” open source programming language developed by Google years ago and some of the reasons for its rising popularity relate to the ease of compiling the same code for different systems, making it easier for attackers to spread malware on multiple operating systems, according to the report.

And specifically, IoT attacks move quickly. Our team has been monitoring the trend of IoT-related vulnerabilities and observing an increased momentum in which they infect and compromise devices. However, while hackers have crafted attack vectors that spread rapidly, it can take weeks (sometimes months and often never) for firmware vendors to discover, resolve, and patch a vulnerability in their devices. In the meantime, many networks will have already been negatively impacted by the exploited vulnerabilities.

For example, here’s a one-week sample of blocked attacks on IoT devices protected by SAM from a sample size of 500K networks – any of which could have led to a DoS/DDoS incident:

Attacks blocked | Compromised devices

[NO-CVE] TVT Shenzhen DVR remote code execution vulnerability

113,209 | 2,317

Generic command injection attempt – wget

46,639 | 3,144

General injection command – dir

45,607 | 242

[CVE-2017-7921] Hikvision backdoor authentication

44,919 | 5,022

General injection command – pwd

42,783 | 294

Generic command injection attempt – wget+

39,150 | 3,003

[CVE-2017-18377] Wireless IP Camera (P2P) WIFICAM – Unauthenticated Remote Code Execution

22,490 | 215

[CVE-2017-7921] Hikvision snapshot disclosure attempt

16,258 | 1,091

General injection command – which

11,950 | 35

Found file disclosure exploit attempt

9,065 | 3,116

Multiple CCTV-DVR Vendors – Remote Code Execution

8,790 | 575

Found telnetd exploit attempt

7,545 | 1,036

Why is protecting consumers from cyberattacks important for telcos?

To protect these devices – and guard against the possibility of a DDoS attack – it is first necessary to accurately identify them and then assess their vulnerabilities and enact preventative measures. Such measures correspond with the three high-level risk mitigation goals identified in the NIST report referenced above, namely:

1. Protect device security – In other words, prevent a device from being used to conduct attacks, including participating in distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks against other organizations, and eavesdropping on network traffic or compromising other devices on the same network segment. This goal applies to all IoT devices.

2. Protect data security – Protect the confidentiality, integrity, and/or availability of data (including personally identifiable information (PII) collected by, stored on, processed by, or transmitted to or from the IoT device. This goal applies to each IoT device except those without any data that needs protection.

3. Protect individuals’ privacy – Protect individuals’ privacy impacted by PII processing beyond risks managed through device and data security protection. This goal applies to all IoT devices that process PII or that directly or indirectly impact individuals.

And service providers have a vested interest in making sure they are identified and protected. An attack can damage a SP’s corporate reputation and relations with customers and incur tremendous costs in repairing the damage, such as onsite visits to repair or replace modems or routers. Other costs include disruptions to the business itself and the loss of sensitive and customers’ personal data. Therefore, based on our long history of device identification and network monitoring, here are some measures service providers can take to enhance security in an increasingly interconnected world.

First, select a security expert that can develop a system that can integrate seamlessly with legacy and new equipment, especially CPE. Such integration should be compatible with the operator’s current service provisioning, billing and support systems. Such compatibility would enable valuable features such as consumer- and business-focused dashboards and apps that can enhance the user experience and make it easier to fully identify all devices on a network (for instance, with brand names and models, not just a MAC address).

Second, a security expert should have a vast database or library of reference points to its own and other security research to show exactly how vulnerabilities can impact the service provider. All of this data can be used to work with the service provider and – by extension – their customers and educate them on ways to avoid security pitfalls. The utility of having such a database can also be seen in the ability to protect users against sophisticated attack vectors. Some security firms without such capabilities focus on phishing and DNS filtering. However, information gleaned from thousands of specific use cases can provide security against a much wider variety of targeted threats.

To conclude, identifying all devices in a customer’s home or office is a good business practice that could have security ramifications beyond the operator’s network. Significant steps have been taken recently in both the private and government sectors to augment device identification capabilities and devise the appropriate protections to ward off DDoS and other attacks. Advanced AI and machine learning techniques have been incorporated into these identification and protection schemes. These techniques are contributing to a much more sophisticated database that will enable a faster identification of – and response to – both known and currently unknown threats.